DePIN Governance Models

From Cold Start to Community Control

Decentralized Physical Infrastructure Networks (DePIN) face a governance paradox. The promise is community ownership and decentralized decision-making. The reality is that physical infrastructure: sensors, nodes, wireless equipment, requires operational accountability that pure token voting cannot provide. How should protocols navigate this tension?

This post examines three governance approaches and argues that hybrid models offer the most viable path for protocols managing real-world infrastructure.

1. Reputation-First Governance: The Right North Star

The most principled approach to DePIN governance is reputation-first: participants earn governance influence through verifiable work rather than token holdings. Operators who demonstrate reliability, uptime, and quality service gain decision-making power. This mirrors how we would ideally select any infrastructure operator: based on track record, not wealth.

The challenge is the cold-start problem. When no one yet has a track record, who governs? Without seeding reputation data, influence concentrates with those closest to the launch team. Filecoin explored miner reputation as a governance signal, but initial control necessarily rested with the Filecoin Foundation and Protocol Labs. Render Network and DIMO followed similar patterns: reputation frameworks were designed, but operational decisions stayed centralized until enough measurable performance data accumulated.

This isn’t a failure of the reputation model rather an acknowledgment that reputation takes time to establish. The question is how to bootstrap governance when decisions need to happen from day one.

2. Token-First Governance: Decentralization Optics with Safety Backstops

Token-first DAOs distribute decision-making immediately, typically via airdrops or liquidity events. Community members vote from day one. This approach delivers on decentralization optics but consistently requires backstops to remain operationally sound.

Consider three prominent examples. Arbitrum launched with immediate community voting but relied on the Arbitrum Foundation to hold the treasury and interpret early proposals. Optimism created a dual chamber system: a Token House for token-weighted votes and a Citizens’ House for reputation-based input, while retaining a foundation board with veto power. ENS ratified its constitution by public vote, but the ENS Foundation continued to implement proposals and manage operations.

The pattern is consistent: token-first optics paired with foundation backstops for safety. For projects managing infrastructure dependencies or regulatory exposure, this duality is a practical safeguard against operational failure while governance matures.

3. Hybrid Governance: The Pragmatic Middle Path

Hybrid governance accepts a simple truth: early-stage protocols need an accountable center, but that center should have a defined expiration date. Staking provides initial economic security and network stability; decentralized governance later provides legitimacy and adaptability.

Most major networks now evolve through predictable stages:

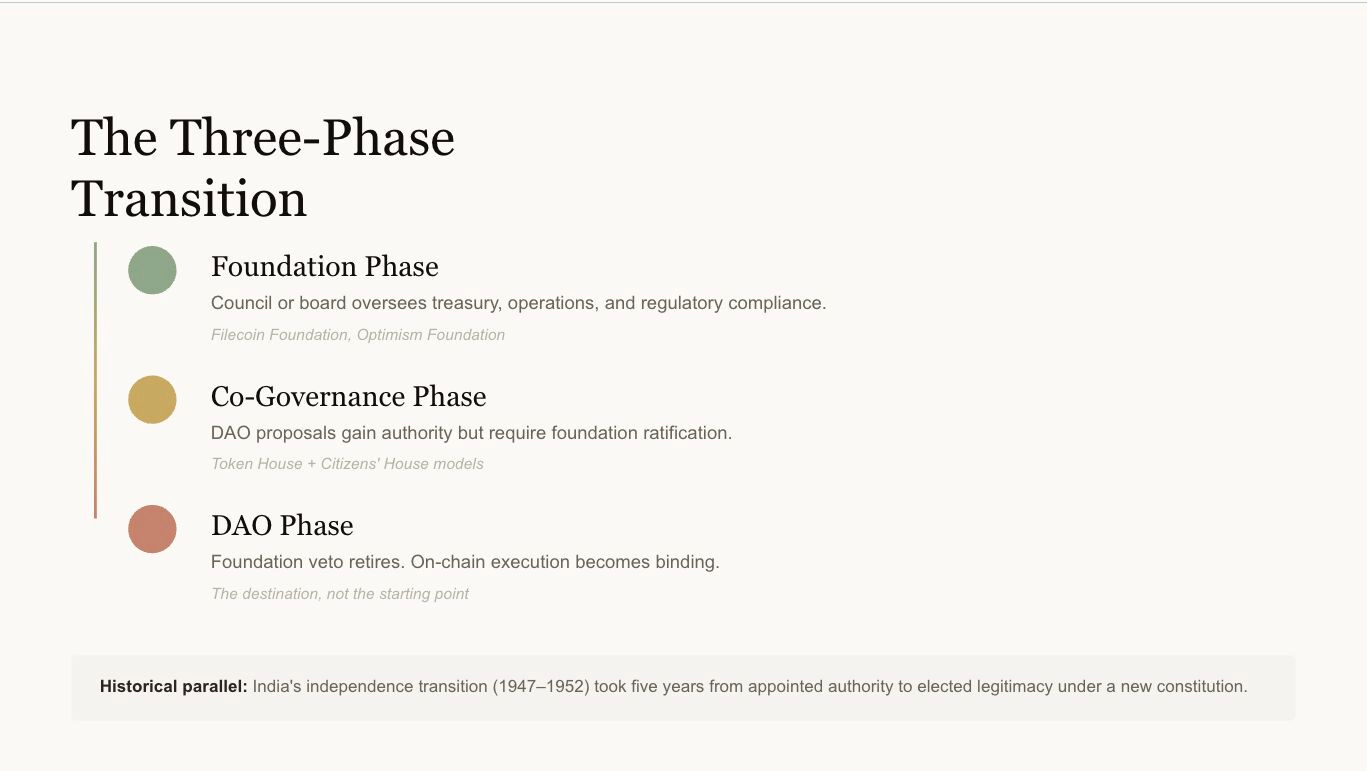

Foundation Phase: A council or board oversees treasury, operations, and regulatory compliance.

Co-Governance Phase: DAO proposals gain authority but require foundation ratification for execution.

DAO Phase: Foundation veto retires and on-chain execution becomes binding.

Filecoin, Optimism, and Arweave each follow this progression, with decentralization milestones tied to specific operational achievements.

For historical perspective, this sequencing mirrors democratic transitions in the physical world. When India gained independence in 1947, the departing British administration installed a functional government of chosen representatives from the Indian National Congress and Muslim League. Over the following years, these representatives drafted a constitution establishing universal suffrage and popular sovereignty. India’s first general election under the new constitution occurred in 1951–52—five years after independence. The transition from appointed authority to elected legitimacy required time, institution-building, and deliberate sequencing.

4. Why DePIN Requires Hybrid Approaches

Physical infrastructure introduces governance challenges that pure economic incentives cannot address. Latency requirements, geographic distribution, regulatory compliance, hardware quality are dimensions that require judgment that token markets alone cannot optimize.

Venture-backed protocols gravitate toward hybrid governance for structural reasons. Investors need identifiable accountability, auditability, and predictable execution in early phases. They also value decentralization as a long-term differentiator and competitive moat. Foundations provide legal clarity initially; DAOs provide adaptability and legitimacy once networks stabilize.

This dual architecture: centralized competence evolving into decentralized legitimacy, has become standard for credible, capital-backed protocols. It addresses the operational reality that governance must handle physical operations, legal compliance, and investor stewardship alongside on-chain coordination.

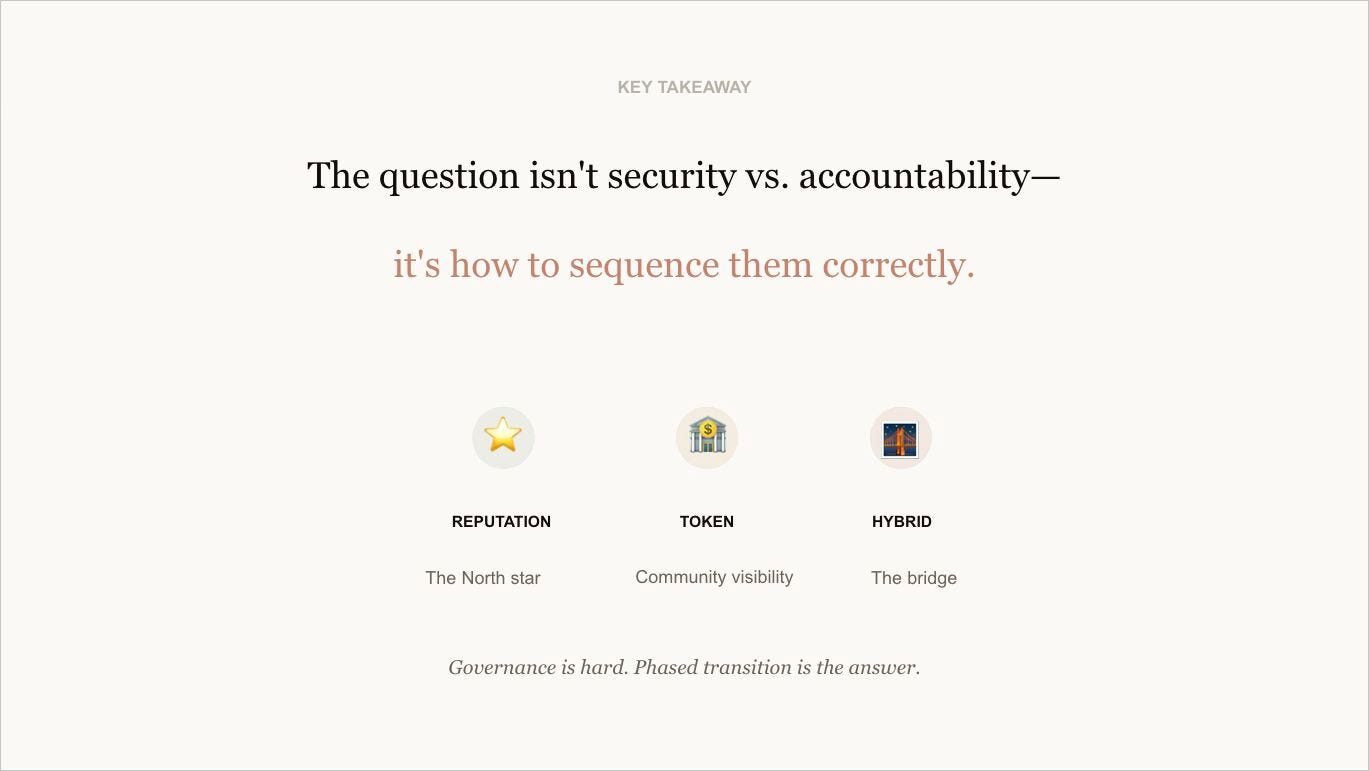

Conclusion: Sequencing Is Strategy

For DePIN protocols, the governance question is not whether to prioritize economic security or community accountability rather, it’s how to sequence them correctly. Reputation-first governance provides the right north star. Token-first distribution brings community visibility and ownership. Hybrid structures offer a bridge between necessary early coordination and eventual autonomy.

The hybrid model offers a pragmatic glide-path from the economic guarantees of staking toward the institutional maturity that real decentralization requires. The test for any protocol is whether it can execute this transition: from foundation oversight to community control, without falling into plutocracy or paralysis.

Governance is hard. A phased transition is the most meaningful approach to address the operational complexity that physical infrastructure demands.